Drawing Fundamentals: The Definitive Guide (2024)

Hey dear reader, I’m glad you clicked on this article!

It’s a 5000+ word beast on the fundamentals of drawing, packed with drawings, learning tips, exercises, and more.

Use the table of contents below to jump to sections that most interest you.

Why an article on drawing fundamentals?

I’m Felix, the author of this blog, and self-taught in drawing and painting.

When I started drawing, I’d get sucked into one way of drawing, e.g. measuring, and completely miss other crucial skills like value drawing, mark making, design, materials & perspective.

All in all, I would have progressed faster, with less bad drawing days along the way, if there was a clear overview of the key fundamentals of drawing.

What you’ll learn

Most drawing problems don’t come from lack of effort — they come from missing or weak fundamentals.

Flat drawings, muddy values, stiff poses, broken anatomy, and “something feels off” sketches are all symptoms of the same issue: the core skills aren’t working together.

When your fundamentals are solid, drawing becomes clearer and more enjoyable. You know how to start a drawing, how to build it step by step, and how to fix problems instead of guessing.

By the end of this guide, you’ll understand which fundamentals actually create realism, how they support each other, and where most artists go wrong when learning them.

Common Beginner Mistakes That Stall Progress

If you’ve been practicing for a while but still feel stuck, you’re not alone. Most artists struggle because they unknowingly make the same mistakes:

Practicing skills in the wrong order

Drawing too dark too early

Relying only on measuring instead of seeing shapes

Copying references without understanding form

Avoiding perspective because it feels intimidating

Never training confident mark making

Jumping into rendering before the structure works

All of these problems come from missing fundamentals — and this article shows you how to fix them.

⭐ Before You Dive In

This article is designed to be genuinely useful on its own — you can apply what you learn here directly to your drawings.

If you’d like faster, more consistent results, and want to see how all these fundamentals actually work together in practice, the Foundations of Realism Course turns the ideas from this article into a connected, step-by-step system. You’ll see each skill demonstrated in video, practice it with structured exercises, and get personal feedback so the fundamentals don’t stay theoretical — they stick.

👉 Check out the Foundations of Realism Course.

Alright, let’s get into it!

How to Use This Guide to Improve Faster

If you’re a beginner, read this guide from top to bottom to understand how realistic drawing skills fit together before diving into details.

If you’re intermediate, scan each section and focus on the fundamentals where your drawings feel weakest — those are your biggest leverage points.

Try 1–2 exercises per section, not everything at once. Improvement comes from focused practice, not volume.

Linear Drawing Fundamentals

Masters of line drawing: Left: Franklin Booth, Top right: Charles Dana Gibson, Bottom right: Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Anders Zorn

Most people start drawing linearly, given it’s how we are taught to write and most issues in realism start here.

Artists struggle with shaky lines, stiff gestures, weak shape design, and outlines that feel dead instead of descriptive. This section teaches you how to avoid those pitfalls.

Key Epiphanies:

Linear drawing can be taken to much higher levels than just measuring & matching lines.

If linear drawing is the “Ying”, tonal drawing is the “Yang. You need to learn both, as they complement each other.

Notice in the master drawings above that beautiful, intelligent and finished drawings are possible just by using lines.

Let’s get into the linear fundamentals of drawing.

Linear Drawing Skill #1: Mark Making

A drawing is a collection of marks you make on paper.

Every mark either makes the drawing more impactful and takes it closer to the finished product you envision, or moves it further away from it.

At a basic level, you have an idea of what mark you want to put on paper. A line that starts somewhere and ends somewhere. And then your hand has to coordinate with your eye and mind to put down that mark.

Mark making is drawing at it’s core, so it’s important to practice it directly.

Chris Legaspi is the teacher who really made me realize how important mark making is.

I was lucky to learn from him in person for 3 days in Thailand (more on that in another article), and we spent a good chunk of it on mark making.

Epiphanies on Mark Making:

Beautiful & confident marks equal beautiful & confident drawings. Scratchy, timid marks equal scratchy, timid drawings.

Each mark you make either takes your drawing closer to the end product, or moves it away from it. It’s one of the reasons why drawing is hard.

Mark making has to be practiced, in the beginning regularly, later as part of warm ups, like a motor skill or a sport.

The difference between a master and a beginner is how many concepts go into each mark.

A master considers perspective, design, lighting, values, composition and many other concepts while putting down one mark. A beginner might just think “Is the angle of my line right”.

Mark making practice is about training your hand in the ability to execute what your mind envisions on paper. It’s the physical skill side of drawing. Think of it like a sport.

The great thing is, you can practice mark making quite easily in your sketchbook.

A few minutes a day and your mark quality will improve dramatically, within a short period of time.

Over time you’ll build a higher baseline of quality mark making habits, and need fewer warm ups.

At that point, you can revisit them whenever you feel your hand loses that precision.

Posture and Positioning

Great mark making starts before you even make a mark - with your posture.

Bad posture vs good posture

3 Elements of Good Posture For Drawing:

Head position

Make sure you always look at the subject from the same point of view.

Keep your head in a position where it can see the subject and the drawing straight on, without much movement.

Distance between your eyes and the drawing

Don’t hunch over and get too close.

Keep the drawing at roughly an arms length. It’s easier to draw from the elbow and shoulder that way and to see mistakes.

Rules are there to be broken

If you can only get a specific mark by turning the page to get into a specific position that’s ok. Just return to your basic posture afterward.

Find a balance of comfort and stable positioning in your drawing posture.

Overall make sure you have a high standard for the physical movement side of drawing, and pay attention to it.

How you sit, breathe, hold your pencil, at what distance and angle you sit to the drawing and subject - it all matters. A little mindfulness already goes a long way.

Alright, let’s get to the exercises:

Linear Mark Making Exercises

Mark making exercises 1 to 3 make for great drawing warm-ups.

Linear Mark Making Exercise 1: Straight Lines

Create 2 dots, connect them with a straight line

Practice these horizontal, vertical & diagonal

Practice these in short, medium, and long length

Practice light, middle, and dark value lines

Combine straight lines into rectangles & triangles (Experiment with mix of curved and straight lines for more dynamic shapes)

Why?

Confidently drawn straight lines of different lengths, angles, and values are a fundamental mark you will make all the time. Being able to draw them accurately and confidently is key.

Combining straight and curved lines into basic shapes.

Linear Mark Making Exercise 2: Curved Lines

Create 2 dots, connect them with a curved line

Practice these horizontal, vertical, and diagonal

Practice these in short, medium, and long length

Practice these in light, middle, and dark value lines

Practice circles and ovals, in different sizes

Why?

Curved lines are another fundamental mark you will make all the time. They can be a bit trickier to draw well at varying lengths, so make sure you practice them. Circles and ovals are also fundamental shapes you’ll use a lot.

Circles and ovals drawn freehand.

Linear Mark Making Exercise 3: S - Lines

Create a few dots, connect them with an S line in one stroke

Practice going over that S line several times, without losing it’s track

Practice it in light, middle and dark values

Why?

Some drawings call for complex marks with unique curves to them, for example when drawing the contour of a human figure or a portrait. Practicing S lines will prepare you to execute them confidently in one stroke when needed.

Practice drawing light, middle, and dark value lines.

Linear Mark Making Exercise 4: Linear Rendering

Practice rendering boxes in 5 values with:

Straight lines: horizontal, diagonal, vertical

Curved lines: horizontal, diagonal, vertical

Why?

Shading your drawing involves hatching lines close next to each other, to get a field of value. Practicing clean value scales trains your mind to render evenly, but also to see values, which prepares you for tonal drawing later.

Drawing value scales with straight lines. Aim for smoothness and quality as much as you can.

Drawing value scales with curved lines. Check out my value scale article to dive deeper.

Hidden Benefits of Mark Making Exercises

Beyond improving the quality of your marks (how they look), the above exercises prepare you for better design and process while drawing.

Mark Making Improves Design

While drawing you simplify what you see into basic lines, shapes, and variations of them. It’s the beginning of design.

Beautifully designed and executed lines and shapes equal (among other things) a beautiful and well-designed drawing.

Mark Making Improves Process

Learning to draw marks from light to dark values, at will, directly applies to your drawing process. You start drawing lightly, and then go darker as you build up the drawing.

Beginners often draw too heavy-handed in the beginning, making bad marks from the early stage shine through in the end. You’ll avoid that mistake by practicing your marks.

Linear Drawing Skill #2: Measurement

To draw realistically, you need to be able to measure.

Meaning, the relationships between the lines you put down should closely match those of your subject.

Key Epiphanies:

Learning to measure and put marks in the right places will dramatically improve your ability to draw realistically.

Measuring is not the end all be all of drawing. You want to get good enough at it to get to the fun stuff like design, gesture, rendering, etc.

Free hand measuring is tough at first but becomes second nature with a few tricks, and is way more freeing and fun than sight-size (in my opinion).

If you read one book on measurement, it’s Betty Edwards “Drawing on the Right Side of The Brain” (Using this affiliate link supports the site and future articles). It’s a well-written classic, that will teach you basic observation skills.

Here are the basics of measurement:

The Lay-in Process Step 1: First Lay-in

Start by laying in the big shapes and lines at a very light value.

The light value is important, so you can correct yourself later. Your mark making practice should come in handy here.

For each line you draw, decide: Is it a straight, curved or S line.

For each major shape you lay in, decide: Is it circular, oval, square or triangular? Congrats, you are designing!

Lay-in portrait drawing example of a photo by Earth’s World.

The first lay-in will never be perfect. But, the more is on paper, the easier it is to judge if your marks are correct.

Once you’re done, take a break, and a step back, look at the drawing and compare it with your subject.

The Lay-in Process Step 2: Check Angles

An easy tool to start seeing angles is the compass.

To illustrate the idea, I put a transparent paper on the drawing and drew a compass on it.

Simply pick a line on your drawing, e.g. the angle of the nose, and then draw it on the compass. This will give you a clear sense of the angle of the line.

From there, compare it to the angle of the line on the reference photo, and adjust if it doesn’t match.

Check angles to improve accuracy.

With that method, check the critical lines of your drawing:

The angle of the forehead

The angle of the hairline

The angle of the ear tilt

The angle of the chin

Etc.

Over time you will do this intuitively with each mark you make.

The Lay-in Process Step 3: Triangulation

Another measurement trick, and one I regularly use while I’m drawing, is triangulation.

You pick a major landmark, e.g. the insertion of the ear, and then check the distance & angle to 2 other landmarks, e.g. the top of the forehead, and the turn of the eyebrow.

Example of triangulation to check measurements.

From there a triangle emerges, which you can compare to the reference.

What matters most is the relationship between the triangle’s parts, rather than the size. Thinking in these triangulations will help you spot measurement mistakes quickly.

Apply this to several major landmarks of the drawing, compare them to the subject, and adjust.

The Lay-in Process Step 4: Plum Lines

Plum lines are simply lightly drawn or imagined lines you use to check if your drawing is correct.

Check the accuracy of your drawing with plum lines.

Pick a point on your drawing, go vertically down and see what it hits. Then check the same plum line on the reference. Does it hit the same spots, or not?

Adjust accordingly.

The Lay-in Process Step 4: Negative Space

This is an effective and often-used measurement trick. Instead of measuring your subject, look at the negative space that surrounds it.

Use negative space drawing to check accuracy of the silhouette.

Then, compare the shape of that negative space to the negative space on the subject. Do they match? If not, adjust.

Summary of The Lay-In Process

Lay-in major shapes and lines

Step back, and check using angles, triangulation, plum lines, and negative space

Adjust

Lay in smaller shapes and lines

Step back, adjust

Lay in smallest shapes and lines

Wash-rinse repeat

How often you step back and correct depends on:

How good you are at getting it right the first time (you’ll improve over time)

How much you care about a realistic look

You’ll collect more measurement tricks over time, but the above should be a great start.

Linear Drawing Skill #3: Shapes

Shapes are the natural evolution of line. By connecting lines you create shapes.

Just like any line can be simplified to a straight, curved or S-line, every shape can be simplified to a circle, rectangle, triangle or oval.

The mark making section should already have prepared your hand for drawing basic shapes.

Now it’s time to understand why shapes are key for great design.

Shape Drawing Exercise: Study Shapes from the Old Masters

To practice shape design, pick a drawing or painting from a master, and simplify it into major shapes.

You can draw them freehand, or use transparent paper at first to get a feel for the exercise.

Here is an example shape study I did with transparent paper on a Giovanni Boldini painting.

Learn shape design from the old masters.

As you can see, the simple shapes of the drawing read very clearly. The shapes alone already communicate the figure.

To get better at shape design, study the shapes of old master paintings. Then apply that thinking to your own drawings.

If you want to go much deeper into shape drawing, check out my definitive guide on drawing with shapes.

Linear Drawing Skill #4: Gesture

I list gestures as a linear skills, as that’s how most get started with gesture drawing.

Similar to perspective, it’s a skill that informs any mark you make, even the tonal ones you’ll learn about later.

Here is an example of a 3min gesture drawing I did recently:

Gesture drawing example, photo by Dynamic Muse.

Gesture drawing is about capturing whatever you draw in as few lines and shapes as possible.

There are no rules to gesture drawing, and there are many different ways to approach them.

You can use any type of mark you want and experiment.

How To Practice Gesture Drawing:

Go to a reference site like “Line of Action” or “Sketchdaily”

Set the timer to 30seconds, 1 minute or 2 minutes

Do a bunch of drawings in a row and try to capture the whole subject within that time frame

Tip: Try and stay loose in your wrist, elbow, and shoulder, and keep a relaxed posture. Don’t rush. Gesture drawing is about good decision-making.

Key Epiphanies:

Gesture drawings improve your longer drawings, and your longer drawings improve your gestures.

The better you know a subject, the more you have drawn it, the easier it will be to simplify it into a few strokes and capture its gesture.

Gesture drawing teaches you to make a few good decisions instead of many bad ones. That increases your drawing speed.

Gesture drawing in many ways is like sketching on location.

Try sketching people when you are at a cafe, at the airport, or on the train. Given the time pressure, you are forced to make a few good decisions about what lines and shapes to draw.

Alright, this was the linear drawing section.

Linear drawing is where many artists feel their drawings look stiff or messy, even when proportions seem right. If you’d like guided demos and exercises that build confident lines, clear shapes, and flowing gesture, the Foundations of Realism Course expands on this step by step.

Tonal Drawing Fundamentals

Tonal drawing is a step towards painting and a way of thinking visually.

If you know nothing about tonal drawing, your drawings might look flat or muddy.

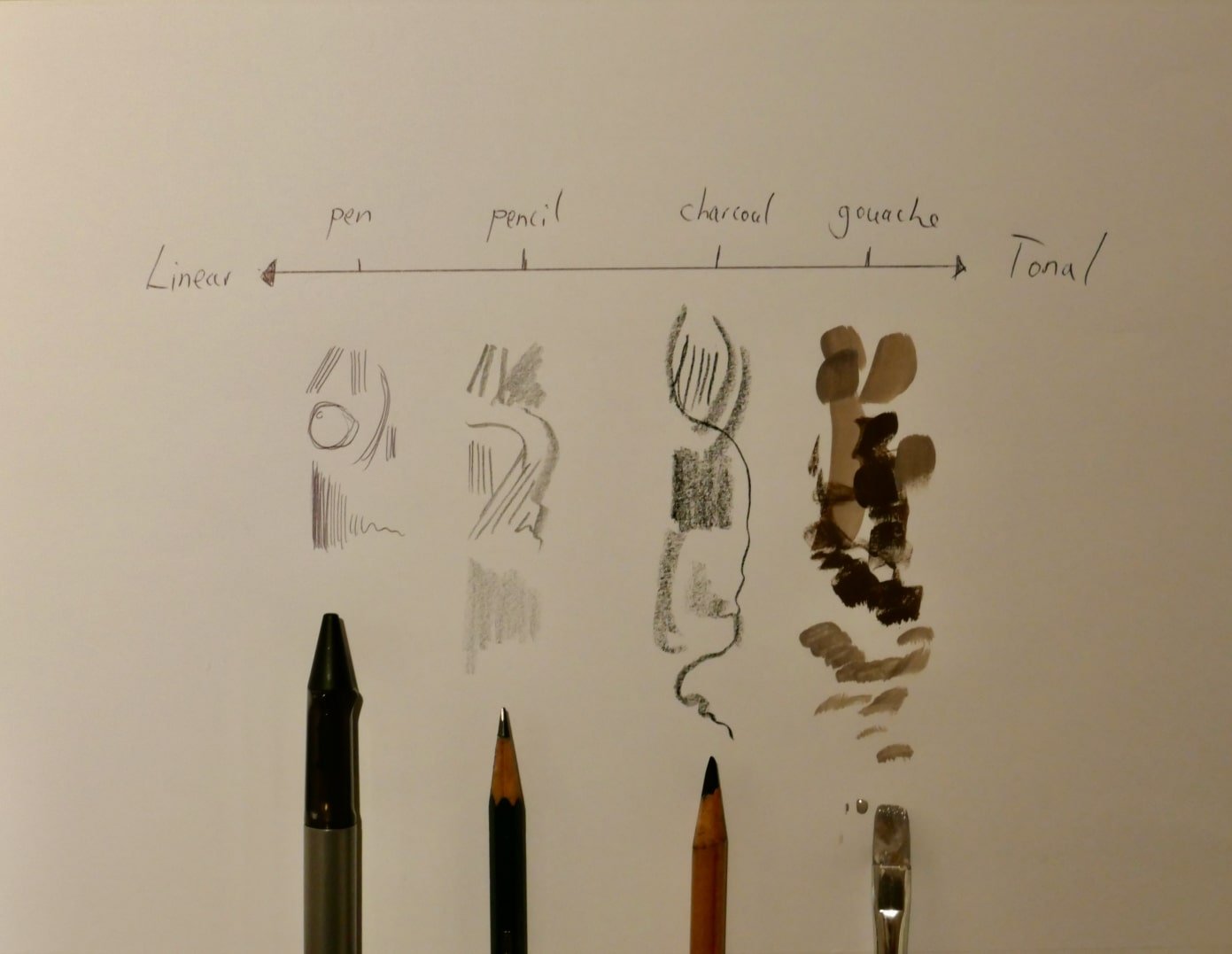

You can think of mediums on a continuum from linear to tonal:

Media from linear to tonal. Each medium offers unique lessons to be learned.

Why Practice Tonal Drawing?

It’s faster to lay in masses of value compared to cross hatching with a linear medium.

It’s easier to create and practice soft edges and transitions compared to pen.

It teaches you lessons you can later apply to your linear media and vice versa.

To transition into tonal drawing I suggest using a pencil or colored pencil.

As you get more practice you can play with charcoal or conté, which tend to be even softer and allow you to lay in large masses of tone quickly, given the bigger lead size.

Once you reach a base level of skill with tonal drawing, you can experiment with painting. It teaches you lessons that improve your drawings.

Alright, let’s get to the basics of tonal mark making.

Tonal Drawing Skill #1: Mark Making

With tonal media, like pencil, conté/charcoal, or paint, you can lay in an area of tone with just one mark.

Compared to linear marks, tonal marks have varying degrees of “broadness” to it.

To understand this, you have to learn the overhand grip and how to sharpen your pencil correctly.

The Overhand Grip

Tonal drawing example with the overhand grip in pencil.

The overhand grip only works with the linear/tonal transition mediums like pencils, colored pencils, conté and charcoal.

Essentially you hold the pencil like a brush, and as a result can make broad marks.

Sharpening the Pencil for Overhand Grip Use

Use a long-lead manual pencil sharpener (e.g. Blackwing) and sharpen to a long point

Round the tip into a “bullet shape”, by rubbing all sides equally on a piece of paper.

Pencil sharpened into a slight bullet shape for tonal marks.

Why I Prefer Graphite Over Charcoal Pencils

You might have seen some artists laboriously sharpen their charcoal pencils with a knife to get a very long tip.

While this definitely gives you the most dexterity, I prefer using graphite pencils because:

They are less messy than charcoal pencils (the powder goes everywhere)

Long-lead graphite pencil sharpeners are easier to carry than sharp exacto knives

Long-tip charcoal pencils are hard to carry and break easily

-> That’s why graphite is a great tonal transition medium for beginners moving from linear to tonal drawing.

Let’s get to the exercises.

Overhand Grip Exercises

Surprise:

All the linear mark making exercises apply to tonal mark marking in the overhand grip.

Simply refer to the linear mark making exercises, and do them with tonal marks instead.

Examples of the overhand grip in action.

Practice making tonal marks as straight lines, curved lines, S lines. Learn to draw shapes with tonal marks and varying gradations of tone.

At first, the overhand grip will feel awkward, but with practice, it’ll feel as natural as your usual writing grip, which you can still use as needed.

Other Tonal Materials

You can learn to draw tonally just with a bullet-shaped pencil and the overhand grip.

But be aware that other materials are out there to experiment with.

Paper stumps, blending tissues, and makeup brushes - they are all tools to soften your marks.

Blending tools to experiment with.

Tonal Drawing Skill #2: Perceiving Values

Perceiving values is about translating the real world values into a value scale that you define before you start drawing.

Here an example of a Sargent study I did:

John Singer Sargent painting studied in pen.

You can see the value scale next to it. The face primarily has white and half tones. The hair has 2 darker values.

For most purposes somewhere between 3-5 values already will give your drawing a lot of “pop”, meaning a sense of three dimensionally.

How to Practice Perceiving Values

Squint at your subject. It helps simplify what you see into value shapes.

Practice reducing subjects into 2-Value, 3-Value. Experiment with different materials (See materials section).

Here are a few 2 & 3-value landscape studies I did. You can also apply this to portraits, figure drawing, and any other subject.

As you can see, these value studies simultaneously help you practice shape design, so they are a double-whammy.

Value studies in marker and white pencil on toned paper.

Tonal drawing is where many artists feel their drawings look flat or muddy, even after lots of shading. If you’d like guided demos and exercises that show how to organize values and light for real depth, the Foundations of Realism Course expands on this step by step.

Form Drawing Fundamentals

If lines are 1D, shapes are 2D, then form is 3D.

Form is about making your drawings feel three dimensional and real. It’s where your linear and your tonal skills meet.

Form has several elements to it:

Perspective: Where does the mark you make start in 3D space and where does it end in 3D space. Perspective is like the linear skeleton of form (Cross contour drawing is a great entry into perspective).

Light & shadow: How the light hits the form determines the value of the different surface planes of your form, and how you model it.

Edges: Sharp or soft value gradations that communicate how the surface planes of your form are shaped.

If you can get a basic understanding of perspective, light & shadow, and edges, you’ll be well on your way to draw realistic looking form.

Form Drawing Skill #1: Basic Forms in Perspective

Perspective is a linear grid that describes the structure of reality.

Drawings that use perspective give you that “This looks like the real world!” feeling.

How To Study Perspective

Like any fundamental drawing skill, perspective is a complex subject.

A basic knowledge will already take you a long way, but you can go as deep into the rabbit hole as you want.

The best free resource to learn about perspective by far is www.drawabox.com.

I also recommend “Perspective Made Easy” by Ernest Norling, for a great intro, and Scott Robertsons “How to Draw” as a life-long perspective guide to refer back to.

Steps to Study Perspective:

Learn to draw basic forms (box, cylinder, sphere, cone) in 1-, 2- and 3-point perspective

Learn to draw form combinations in perspective with grids

Learn to draw form combinations in perspective free-hand

Step 3 is what will allow you to apply perspective to portraits, figure drawing, and more.

Perspective Exercise: Study Form from the Old Masters

Once you can draw basic forms in perspective, start studying how masters simplified their subjects into basic forms in perspective.

Simply pick an old master painting you love, and simplify it into basic forms. You can either draw free-hand or trace over transparent paper.

Here is an example of a Joaquín Sorolla form study using transparent paper.

Learn form design from master paintings.

As you can see, masters simplify what they see into simple forms that read clearly.

Clear form design is just as important as clear line and shape design. It also makes shading your forms much easier later on.

By doing master studies, you will build a visual catalog in your mind of how to simplify complex subjects into basic forms sketched in perspective.

Over time it will become an intuitive skill that greatly increases the realism of your drawings.

Form Drawing Skill #2: Shading Basic Forms in Perspective

Once you can draw basic forms in perspective, shading is the next step.

Here an example of a shaded sphere:

Sphere modelled in form light.

Areas of study to shade forms in perspective:

Lighting scenario:

Is it front, form, rim or back lighting?

How many light sources are there & where are they?

Is the light directed or diffuse (soft)?

Modeling form theory

Highlight

Halftone

Core shadow

Reflected light

Cast shadow

Modeling form is a big subject that goes beyond this article, but a great book that covers all of the concepts listed above is Scott Robertson’s “How to Render” (affiliate link - supports the site and future articles).

In portraiture or figure drawing, you will often use form-light, as it gives the most “pop”, so start studying that. It’s what you see on the sphere above.

From there you can move on to drawing more complex lighting scenarios, and eventually even change the lighting scenario of a drawing.

Form Drawing Skill #3: Edges

Edges took me a while to see, and a while to learn how to draw. I’m still working on it today.

In essence, edges communicate the transition between two surface planes.

2 Hacks to See Edges

Check the value difference between shapes. The wider the difference, the harder the edge, The narrower the difference, the softer the edge.

Check the gradation between shapes: The slower the gradation turns, the softer the edge, the faster the gradation turns, the harder the edge.

Model edges using value differences and gradations between shapes.

Once you understand value differences and gradations, I recommend copying drawings by masters with these concepts in mind.

I learned a lot from studying drawings by Henry Yan, as he very clearly designs edges and value in his charcoal drawings.

Here’s a recent drawing I did of a Marylin Monroe vintage photo.

Toned paper drawing of a Marylin Monroe vintage photo using edges.

Compare the value difference of the forehead to the hairline to that of the chin to the neck. You can see subtle differences in the edges.

A little bit of edge design already goes a long way.

Form drawing is where many artists feel things “should” make sense but don’t quite click. If you’d like guided demos and exercises that show how to build real volume and depth, the Foundations of Realism Course expands on this step by step.

Picture Making Fundamentals

Once you understand line, shape and form fundamentals, it’s time to learn about picture making.

Some might consider this more advanced, but really it’s a fundamental drawing skill.

Picture Making Skill #1: Subject Knowledge (Anatomy)

The better you know a subject, the easier it will be to draw it.

Key Epiphanies:

To draw portraits and the human figure, learning anatomy is key.

To draw animals, learning animal anatomy is key.

To draw landscapes it’s important to study textures and patterns of plants, stones, and other objects in nature.

In this section, we’ll focus on human anatomy as an example, but you can apply it to other subjects equally.

How To Study Anatomy

The easiest way to study anatomy is to get a few great anatomy books for artists. I recommend those to start with:

(support this site by using the affiliate links above)

From there you pick an area of the body that you struggle drawing, find a couple of anatomy references, and draw them free-hand.

Don’t forget your other drawing skills, don’t mindlessly copy. Instead, make sure to design.

Tips for studying Anatomy:

It’s critical to pay attention to muscle insertions. Where do muscles start and end? How they insert is pretty universal.

Pay attention to the simplified form of each muscle. Of course this varies by person, but a bicep has a very typical shape that’s different from the leg muscles, and so on.

Learn about the function of the muscle as well. It will help you draw expressions on the face and the figure in action.

Here are two exercises I use to study anatomy myself with sample drawings.

Anatomy Exercise 1: Linear Anatomy Studies in Pen

I’ve found quick pen studies of anatomy book references help internalize muscle insertions, as well as understand where beautiful gesture lines are on the body.

Here is a recent study of mine:

Anatomy drawing on toned paper, study of male arm in pen.

Pen studies are fast, so you can study many body parts in one session.

It’s as simple as getting a few anatomy books, and drawing the body part references you find interesting.

Feel free to add notes next to it to name the muscles, or to list it’s function.

Tips:

Don’t just copy, also design. Simplify lines into straight, curved and S lines, and use basic shapes.

Draw from the wrist for small lines, from the elbow for medium lines, and from the shoulder for long lines.

Anatomy Exercise 2: Tonal Anatomy Studies in Colored Pencil

Muscles and bones are forms, with varying degrees of soft and hard edges, round and flat surface planes.

Tonal anatomy studies are a great way to study an area of the body in detail, to really understand how light & shade, edges, and form apply to that body part.

Anatomy drawing study of male arm, colored pencil on toned paper.

For the study above I used a Strathmore toned grey sketchbook, Prismacolor Verithin & Premier for the darks, and Prismacolor Colerase & Premier for the whites.

Check the material section for more details.

The Prismacolor Premier line tends to give darker darks and whiter whites and is great for that complete tonal range.

Anatomy Exercise 3: Study Proven Visual Models

Many great artists created simplified versions of the head or figure to teach students key visual aspects of them. I call them visual models.

By studying those visual models you understand how the artist designed and thought while drawing.

You will also pick up a few shortcuts you can apply to your own drawings.

I can’t go into all of them in this article, but here is the list of the most well-known models, that are worth studying:

Famous visual models:

Azaro head & figure sculptures

Great for studying surface planes

Andrew Loomis head and figure models

Great for figure proportions and simple portrait construction

Rythmic lines that move through the head and figure

Burne Hogarth Figure and head models

Figure and head construction models that favor a spherical, round design

Simply draw them, and you’ll find they stay with you next time you do a drawing of your own.

From there do as Bruce Lee said:

"Absorb what is useful. Discard what is not. Add what is uniquely your own." -Bruce Lee

Picture Making Skill #2: Materials

Different media teach you different lessons more easily:

I learned a lot about perspective, and cross-contour mark making using pen, which then helped me with modeling edges in my tonal drawings.

I learned a lot about value scales from painting, which improved my linear pen drawings.

Each medium has it’s strengths, and weaknesses, and as a result teaches you different lessons.

Paper also matters a lot. Smooth paper makes it easier to draw smooth edges. Grainy paper gives your drawings a grainy look.

All in all the main lesson is you have to experiment.

Get a few papers, from smooth to rough, then do your mark making exercises in different media on them.

My Materials & Home set up:

Top left:

Pencil case for travelling. I regularly check, clean and rearrange what materials I take, depending on what I’m focused on practicing.

Top right:

A bunch of markers (greys and black), brush and Micron pens. The markers are great for value studies, the brush & Micron pens for inking and vignettes.

Bottom left:

Sketchbook with smooth white paper from Leuchtturm. You have to try papers until you find one you like. Smooth paper creates smoother effects when drawing.

Faber Castell graphite pencil B. I usually have a few different strengths.

Mechanical pencil for finer details. Again you can get them in different diameters and strengths.

Wollfs Carbon charcoal pencil: I don’t use it as much, but always got it with me. Out of all charcoal options this and the Conté de Paris are the least messy.

Bottom right:

Strathmore toned grey sketchbook. Helps play with white and black colored pencils to get full value range faster.

Ruler for frames.

Prismacolor Verithin Black for darks, Prismacolor Premier Black for darkest darks.

Prismacolor Colerase White for halftones and lights, Prismacolor Premier White for highlights.

Long-lead pencil sharpener by Blackwing: Great for sharpening pencil to a long-lead while on the go.

Different erasers for details.

While I use the sketchbooks on the go, my home setup looks like this:

Screen connects to Macbook via HDMI cable. Allows me to pull up drawing references on the screen.

Easel was a cheap one from Amazon, around 30€ if I remember correctly.

Simple plastic pencil organizer from Muji.

And lots of art books you can’t see here all over the apartment.

Tips for Choosing Materials

A smooth white paper sketchbook, a pencil and a pen, a long-lead pencil sharpener and an eraser is all you need in the beginning.

Over time you’ll want to experiment with markers, fine liners, brush pens, colored pencils and toned paper. You can get some nice effects with different materials.

You have to experiment yourself to find what you like.

That’s it on materials!

Picture Making Skill #3: Composition

Composition is the arrangement of lines, shapes and masses of value into a unified whole.

Notice how William-Adolphe Bouguereau arranged the lines, shapes and value masses.

Practically, it’s about taking a breath before you start drawing, and asking yourself some of these question below.

What’s the frame of the drawing, is it square, circular, or rectangular?

How does the subject relate to it’s frame?

What’s the focal point of my drawing, what is the focus? Where do I want viewers to look?

How can I arrange shapes, tones and lines to guide the viewers eyes to the focal point, for maximum impact?

Notice how Joaquín Sorolla directs your eye through composition.

These are just some basic questions. Over time you will develop better compositional questions of your own.

Two GREAT books I recommend reading on composition:

Edgar Payne’s “Composition of Outdoor Painting”

“Mastering Composition: Techniques and Principles to Dramatically Improve Your Painting” by Ian Roberts

(affiliate links - support the site and more articles by using them)

For now, remember:

Most beginners jump into the drawing.

Composition is about taking a second to plan out the visual pattern of your drawing before you start, then keeping it shine through as you build out the drawing.

Picture Making Skill #4: Design

If composition is an arrangement of lines, shapes, forms and values on a macro level, then design is about the visual decisions you make with every mark of the drawing.

Before starting a drawing, ask yourself:

What do you like about this image/subject?

Why would you enjoy drawing it?

What do you want to communicate with your drawing, and how can you maximize that with each decision you make?

Should your lines be smooth, long, and fluid, or zig zaggy and full of tension, like the Van Gogh drawing below?

Notice how Van Gogh designs the lines of the trees.

Should your shapes be balanced, harmonious, relatively neutral, like the ones below by Paul César Helleu? Or pushed to their extreme, dynamic, and exaggerated?

Example of neutral, harmonious lines and shapes designed by Paul César Helleu.

Should you model edges to perfection, or simply indicate them (like in ink drawings)?

Which medium is best suited for this? Should you mix media?

Should you use color or not?

Should you keep the original lighting and value pattern, or should you invent new lighting?

And many, many more…

Design is the result of visual decision-making like this. Of course, you can and should come up with your own questions.

Most beginners just don’t consider these decisions, or make them unconsciously.

The better you get at making conscious design decisions, the clearer you can communicate your vision to other people.

Closing Thoughts

That’s it, I hope you learned something!

You can already apply what you’ve learned in this guide to your next drawings.

If you’d like help turning these fundamentals into a clear, repeatable practice — with demonstrations, exercises, and feedback — that’s exactly what Foundations of Realism is designed for. It builds directly on the ideas in this article and shows you how to train them as one connected system.

Learn more about the course here → Foundations of Realism.

Until next time!